STEP Matters 204

- Default

- Title

- Date

- Random

-

We have written several times about Mirvac’s proposal to develop the land at 55 Coonara Ave, West Pennant Hills that…Read More

-

The local residents living near Mimosa Oval, Turramurra that is part of Rofe Park have been campaigning strongly against Ku-ring-gai…Read More

-

Mermaid Pool, a rock pool below Manly Dam was named in the 1930s for the naked girls who used to…Read More

-

Australia and the world have been horrified by the devastating bushfires that have been burning along the east coast and…Read More

-

In November the results of an aerial survey of feral horse numbers was released. The numbers have increased by more…Read More

-

The decline in koala numbers in NSW has been highlighted over many years by environment groups. The major causes have…Read More

-

Currently there are several reviews taking place into biodiversity management at the federal level: Senate inquiry into faunal extinction review…Read More

-

After a prolonged process of research, impact assessment, economic analysis and discussion with residents the Lord Howe Island Board got…Read More

-

At the start of the bushfires right up to December the government refused to talk about the influence of climate…Read More

-

While we may stand on a clifftop lookout and gaze in awe at its world-class sandstone scenery, it wasn't the…Read More

-

The state and federal governments are unwilling to discuss the issue of Australia’s population growth. The general view is that…Read More

Good News Regarding the Mirvac Decision

We have written several times about Mirvac’s proposal to develop the land at 55 Coonara Ave, West Pennant Hills that contains the old IBM corporate headquarters plus a large area of forest. IBM sold the site to Mirvac in 2010 but stayed on as a tenant until September this year. Mirvac’s proposal was for the development of a 600 dwelling complex that would result in the loss of many mature trees including Blue Gum High Forest and Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest. The future responsibility for management of a large forested area below the new housing areas was left unknown.

In order for the development to proceed the Hills Council needed to vote in favour of the rezoning of the land from its current classification as a business park to various residential zonings plus an E2 zoning for the forest. The vote was due to be held at the council meeting on 26 November. Naturally the council was recommending approval.

The local community has been objecting to the development for over two years. Many meetings have been held and large numbers have sent submissions and signed petitions. When the item was placed on the meeting agenda the community united again to remind the councillors of their opposition with over 4,000 submissions.

The Forest in Danger group was overjoyed to learn that council voted against the proposal. It was a tied vote of six all with Mayor Michelle Byrne using her casting vote to refuse the proposal.

Councillors who spoke against the proposal expressed the arguments that:

- the proposal is inconsistent with the district plans

- whole of area planning should take place not spot rezoning

- business zones should not be rezoned for housing – Hills has met their housing targets but are short of business zones

- lack of infrastructure

- the significant impact it would have on this sensitive environmental site

- the large amount of community concern about this development

A couple of councillors put in a last-ditch attempt to submit a rescission motion but this was soon seen to be very bad form so the council decision stands. Who knows what Mirvac will do next?

Synthetic Turf at Mimosa Park

The local residents living near Mimosa Oval, Turramurra that is part of Rofe Park have been campaigning strongly against Ku-ring-gai Council’s proposal to install synthetic grass on the oval. The vote was taken on 10 December and the residents were much relieved when council resolved to not proceed with installation on the grounds that:

- the oval is impacted by the Vegetation Category 1 bushfire zone and the proposal presents an unacceptable fire risk

- the oval is surrounded by Rofe Park and Sheldon Forest comprising Ku-ring-gai’s only Biodiversity Stewardship Site

- the proposal cannot accommodate informal recreational use currently enjoyed by the community

Promising Proposal for a Small Bird Habitat Corridor along Manly Creek

Mermaid Pool, a rock pool below Manly Dam was named in the 1930s for the naked girls who used to swim in it. The beauty was lost when suburbia arrived and the pool became a dumping ground for rubbish. The bush was not held in very high regard in those days! But some locals saw the potential beauty of the area and its importance as a wildlife and vegetation link between Manly Dam and Millers Reserve. They got together to save the bushland and waterway.

In the first exercise on Clean Up Australia Day in 2002 over 4 tonnes of waste was removed from the creek including old ovens, car parts, trolleys and building materials. Ever since, the Save Manly Dam Catchment Committee has been working converting the area into high quality bushland. More about the story of Mermaid Pool can be found here.

The Committee has developed a proposal to create a small bird habitat corridor on some Crown land parcels that are currently zoned for potential residential development. The land is close to Mermaid Pool and along Manly Creek but is bounded by low density residential development to the north and south.

Rare bushland has already been lost nearby through the development of Manly Vale Public School. The Species Impact Survey conducted for this school development identified the presence of many species of small birds. Upstream at Manly Dam Reserve (Manly Warringah War Memorial Park) over 80 bird species have been recorded. The proposed corridor is particularly suitable for small birds due to large areas of dense undisturbed vegetation, connectivity with surrounding reserves and refuge from predation and harassment by aggressive species like noisy miners and other impacts associated with the urban environment.

The Northern Beaches Council and local MPs have supported changing the zoning of these parcels to Public Recreation. In August 2019 the Department of Planning made a Gateway Determination in favour of the proposal. The rezoning process has progressed to the stage where council has called for public submissions on the proposal. The final hurdles are likely to have been overcome. Ultimately it is hoped it will be given the status of a Wildlife Protection Area.

Impact of Bushfires on Biodiversity

Australia and the world have been horrified by the devastating bushfires that have been burning along the east coast and tablelands and South Australia since September and reached their climax in December and January. These events have given the world a stark example of the extreme events that will be experienced as a result of climate change. The severe drought conditions combined with weather systems that delivered hot westerly winds followed by strong southerly changes created severe and unpredictable fires. On top of the impact on fire fighters and communities, the long-term impact on biodiversity will become apparent over many years. The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (the department) has done a preliminary assessment of the areas affected by fires using satellite imaging.

As the department states, the period immediately after a fire is critical for the survival of injured animals and for threatened species. The priority is to support those involved in the recovery of injured wildlife and detailed data on the damage to habitat is essential for planning the next steps to minimise the long-term loss of ecosystems.

As of 10 January 2020, the data available reveals that:

- 5.128 million hectares (6.4%) of NSW has been affected by the wildfires. The severity of fire within this total area varies.

- More than 35% of the national park estate (or 2.539 million hectares) has been impacted. In key bioregions, the figure is well over 40%.

- More than 80% of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and 54% of the Gondwana Rainforests World Heritage Area have been affected by fire.

- The most affected ecosystems are rainforests (35% of their state-wide extent), wet sclerophyll forests (41%) and heathlands (53%).

- More than 60 threatened fauna species have been affected by the fires, including 32 species for which 30% or more of all recorded locations occur in the burn areas.

As at 10 January 2020, the bushfires had impacted on the habitat of at least 60 threatened species listed under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

The intensity of the fires has varied widely. In this initial assessment, the department developed a new methodology using Google Earth imagery which enabled the rapid estimate of where fire skipped over an area within the fire ground, leaving it little affected, where it burned the understorey and some of the canopy, where it burned the canopy only, and where it appears to have burned all vegetation.

Once it is safe to do so and ensuring that the environment is not damaged inadvertently, the department is carefully preparing a more refined version of this data for each fire ground, which utilises reference data gained from aerial imagery and ground-based post-fire surveys to provide a more detailed understanding of this variation.

Impact on Threatened Fauna

The department has compared the records of 300 threatened fauna species with bushland affected by the ongoing fires.

As of 10 January 2020, fires have burnt in:

- 70% of the bushland where six threatened animal species were previously sighted include the Long-footed potoroo, Philoria pughi (a frog), Hastings River mouse and Brush-tailed rock-wallaby

- 30% of the bushland where 32 threatened animal species were previously sighted

- 5% of the bush areas where 114 threatened animal species were previously sighted

As of 6 January 2020, more than 24% of all koala habitat in eastern NSW was within fire-affected areas. The total area of highly suitable koala habitat affected by fire in eastern NSW was more than 19%.

The data is being renewed as staff get the opportunity to check the situation on the ground.

Threats to Recovery

In the flurry of announcements of funding for bushfire recovery it is hard to get a perspective on funding that has been provided to prevent loss of animals that have survived. $50 million sounds good but this is against a background where funding for environmental management has been cut by Coalition governments. Will extra staff be employed to carry out the work required?

Recovery will involve the following stages:

- rescue of injured animals

- providing survivors with food and water

- prevention of damage to unburnt bushland from the extra browsing pressure, particularly from feral animals

- removal of feral predators such as cats and foxes

Will the NSW Government Amend its Policies?

There are two areas where the NSW Government has perverse policies.

Feral Horses in Kosciuszko National Park

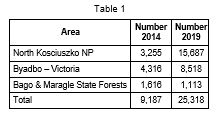

In November the results of an aerial survey of feral horse numbers was released. The numbers have increased by more than 170% in the past five years. In the most populated area, North Kosciuszko National Park, the 2019 numbers are almost five times the 2014 numbers (see Table 1).

These numbers of horses are having a huge impact on alpine species and ecosystems. Horses create tracks through alpine swamps causing the water to drain away. They damage vegetation along streams that are essential for the survival of threatened species such as the Corroboree frog and Stocky Galaxia fish. These streams are the headwaters of the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers. Horses also pose a risk on roads.

The North Kosciuszko area, that has the highest number of horses, is also an area badly affected by the fires. So, the horses will move into the undamaged parts of the north placing great pressure on alpine vegetation already stressed by drought.

The NSW Government has virtually completely cut the program to remove the horses from the park. Only 99 were removed in 2019 and none in 2017 and 2018. Thanks to the influence of the leader of the National Party, John Barilaro, the horses are treated as having heritage value despite the huge damage they are doing to the sensitive alpine vegetation and animal species. The successful program of aerial culling has been terminated.

Hope for change now rests with the new feral horse management plan being developed by the recently established Kosciuszko National Park Wild Horse Community Advisory Panel and the Wild Horse Scientific Advisory Panel.

The Scientific Committee said the draft plan for action will be open for comment in February 2020 to meet NSW environment minister Matt Kean’s deadline for a final plan by 1 May 2020. This rapid timeframe is essential as substantial control measures should be implemented straight away before winter conditions arrive.

Clearing of Koala Habitat

The decline in koala numbers in NSW has been highlighted over many years by environment groups. The major causes have been land clearing for agriculture, forest logging and urban development. A significant part of koala habitat in NSW is in state forests or private land. The forests will recover after the fires but in the meantime the precarious situation for koalas will worsen.

Before this summer’s bushfires, koala populations in NSW and Queensland had already dropped by 42% between 1990 and 2010, according to the federal Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

The mid-north coast is home to a significant number of Australia’s koalas, with an estimated population between 15,000 to 28,000. It is estimated that 30% of their habitat was destroyed in the November/December fires in that area.

NSW Forestry Corporation is still logging unburnt koala habitat in state forests. It is believed that the NSW Government is planning on privatising the Forestry Corporation. The initial focus will be on selling softwood plantations but, as the organisation shrinks, the rest of the organisation will be regarded as uneconomic and the native forests will be next. It is reasonable to expect that private owners are likely to expect a higher profit and hence more rapid harvesting. The principle of sustainable harvesting has been compromised before.

The major clearing is occurring in the inland woodlands where the push is for agricultural development. Grazing land can allow for trees to be retained to shelter stock and provide bird habitat. The push has been to total clearing to make it easier for machinery to plough, plant and harvest vast swathes of land. The value of this cleared cropping land increases dramatically. What will its long-term value be when the nutrients and carbon in the soil have been blown away in dust storms?

As for clearing for urban or tourist development, the State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019 has been changed recently. It clarifies the definition of core koala habitat and increases the number of tree species that can be used to identify koala habitat from 10 to 123. 99% of identified koala habitat on private land in NSW was at risk of being cleared before these changes and that remains the case.

On a more hopeful note the NSW Government has allocated $20 million for the purchase of private land that is core koala habitat to be converted into the reserve system. The NSW Koala Strategy is part of a long-term vision to first stabilise, then increase, koala population numbers across the state. Through many of its actions, it will also contribute to protecting other threatened species.

The NSW Government has committed $44.7 million to support the implementation of the NSW Koala Strategy.

With the sudden loss of so much koala habitat the logging contracts must be reassessed. There is talk that the numbers of koalas killed has tipped the population into the threatened category. It is hoped that the population assessment is made before the loggers can move back in to unburnt habitat.

Will the NSW Government Amend its Policies on Feral Horses?

In November the results of an aerial survey of feral horse numbers was released. The numbers have increased by more than 170% in the past five years. In the most populated area, North Kosciuszko National Park, the 2019 numbers are almost five times the 2014 numbers (see Table 1).

These numbers of horses are having a huge impact on alpine species and ecosystems. Horses create tracks through alpine swamps causing the water to drain away. They damage vegetation along streams that are essential for the survival of threatened species such as the Corroboree frog and Stocky Galaxia fish. These streams are the headwaters of the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers. Horses also pose a risk on roads. The North Kosciuszko area, that has the highest number of horses, is also an area badly affected by the fires. So, the horses will move into the undamaged parts of the north placing great pressure on alpine vegetation already stressed by drought.

The NSW Government has virtually completely cut the program to remove the horses from the park. Only 99 were removed in 2019 and none in 2017 and 2018. Thanks to the influence of the leader of the National Party, John Barilaro, the horses are treated as having heritage value despite the huge damage they are doing to the sensitive alpine vegetation and animal species. The successful program of aerial culling has been terminated.

Hope for change now rests with the new feral horse management plan being developed by the recently established Kosciuszko National Park Wild Horse Community Advisory Panel and the Wild Horse Scientific Advisory Panel.

The Scientific Committee said the draft plan for action will be open for comment in February 2020 to meet NSW environment minister Matt Kean’s deadline for a final plan by 1 May 2020. This rapid timeframe is essential as substantial control measures should be implemented straight away before winter conditions arrive.

Clearing of Koala Habitat: Another NSW Government Decision Required

The decline in koala numbers in NSW has been highlighted over many years by environment groups. The major causes have been land clearing for agriculture, forest logging and urban development. A significant part of koala habitat in NSW is in state forests or private land. The forests will recover after the fires but in the meantime the precarious situation for koalas will worsen.

Before this summer’s bushfires, koala populations in NSW and Queensland had already dropped by 42% between 1990 and 2010, according to the federal Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

The mid-north coast is home to a significant number of Australia’s koalas, with an estimated population between 15,000 to 28,000. It is estimated that 30% of their habitat was destroyed in the November/December fires in that area.

NSW Forestry Corporation is still logging unburnt koala habitat in state forests. It is believed that the NSW Government is planning on privatising the Forestry Corporation. The initial focus will be on selling softwood plantations but, as the organisation shrinks, the rest of the organisation will be regarded as uneconomic and the native forests will be next. It is reasonable to expect that private owners are likely to expect a higher profit and hence more rapid harvesting. The principle of sustainable harvesting has been compromised before.

The major clearing is occurring in the inland woodlands where the push is for agricultural development. Grazing land can allow for trees to be retained to shelter stock and provide bird habitat. The push has been to total clearing to make it easier for machinery to plough, plant and harvest vast swathes of land. The value of this cleared cropping land increases dramatically. What will its long-term value be when the nutrients and carbon in the soil have been blown away in dust storms?

As for clearing for urban or tourist development, the State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019 has been changed recently. It clarifies the definition of core koala habitat and increases the number of tree species that can be used to identify koala habitat from 10 to 123. 99% of identified koala habitat on private land in NSW was at risk of being cleared before these changes and that remains the case.

On a more hopeful note the NSW Government has allocated $20 million for the purchase of private land that is core koala habitat to be converted into the reserve system. The NSW Koala Strategy is part of a long-term vision to first stabilise, then increase, koala population numbers across the state. Through many of its actions, it will also contribute to protecting other threatened species.

The NSW Government has committed $44.7 million to support the implementation of the NSW Koala Strategy.

With the sudden loss of so much koala habitat the logging contracts must be reassessed. There is talk that the numbers of koalas killed has tipped the population into the threatened category. It is hoped that the population assessment is made before the loggers can move back in to unburnt habitat.

Following the Fires – Time to Reboot Biodiversity Management

Currently there are several reviews taking place into biodiversity management at the federal level:

- Senate inquiry into faunal extinction

- review of the Biodiversity Conservation Strategy

- review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC Act)

The outcomes of these reviews will be important in setting policies for the long-term survival of Australia’s unique biodiversity.

In the shorter term there is vital work to be done in ensuring that the wildlife that has survived the drought and fires has sufficient food and water and is not overwhelmed by feral animals such as cats and foxes. The major work will be in bushland to ensure it not invaded by weeds or pillaged by feral horses and deer.

Funding for biodiversity management at the federal and state level has been cut severely since the coalition came into power in 2013. Surely, after the massive bushfires governments need to reassess their priorities for biodiversity management. The media focus has been on the rescue of cute and cuddly animals. Even their long-term survival depends on restoration of habitat.

STEP Matters has included articles about Australia’s biodiversity strategy before. In Issue 194 we lamented the inadequacy of the 2010–2030 strategy. In summary it was at the level of simplistic statements with no quantification of targets. Instead it linked to various strategies that are to be adopted by the states and territories.

It is pleasing to report that progress has been made. On 8 November 2019, Australian, state and territory environment ministers endorsed a new approach to biodiversity conservation through Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019–2030. The strategy is supported by a dedicated website, Australia’s Nature Hub. Both the strategy and the hub are owned by all the governments involved.

The strategy is coordinated with the Aichi Biodiversity Targets under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. These targets are meant to be in place by 2020. We are a bit late but at least we have started.

The strategy provides an adaptive approach allowing each jurisdiction the flexibility to establish targets appropriate to the variety of environments across Australia and to change these as we continue to build knowledge during the life of the strategy.

It does acknowledge the scale of our biodiversity crisis and the role of science in finding solutions. For the first time there is explicit recognition of the need for management to allow for climate change.

An example of the goals is ‘reduce threats to nature and build resilience’. There are six progress measures under this goal, but most are not anything that can be measured, for example ‘retention, protection and/or restoration of landscape-scale, native vegetation corridors’.

A baseline is needed in order to assess progress in achieving this sort of goal. Following the fires, we may need two baselines for many species and vegetation communities – pre-fires and post-fires.

In a positive move the strategy sets an accountability framework, with ongoing working groups and four-yearly reporting, and should drive collaboration between federal agencies, the states and territories on nature conservation – all welcome moves. Fingers crossed that there is the will to progress the strategy beyond statements of the problems and the desire to fix them.

The amount of funding provided for the implementation of the strategy by all the jurisdictions involved is unknown. In the short term, funding will be focussed on fire recovery. Federal funding for the environment department has been cut.

The legislation to support the strategy at the federal level is the EPBC Act. It is currently under review – see below. The shortcomings of the NSW biodiversity legislation will be a stumbling block.

The Nature Hub is a link to projects and strategies that have been adopted so far. There is not much information there yet so the implementation mechanisms for most objectives are unclear.

For example, the national Threatened Species Strategy that commenced in 2016 has goals to tackle the feral cat problem, create safe havens for species at risk from feral cats, improve habitat and apply emergency interventions to avert extinctions. Targets to measure success are:

- 2 million feral cats culled by 2020

- 20 threatened mammals and 20 threatened birds improving by 2020

- protecting Australia’s plants

- improving recovery guidance

Senate Inquiry into Faunal Extinctions

This enquiry commenced in June 2018 and provided an interim report in April 2019 just prior to the federal election at which point the enquiry automatically folded.

The main points in the interim report were:

- Our lack of knowledge about fauna species – estimates suggest that, at present, there are 250 000 faunal species in Australia, with around 120 000 of these yet to be scientifically documented.

- We have a damning track record with a continuing decline in mammal species and a very significant slump in bird populations.

- Evidence given to the enquiry raised serious questions about the ability of the EPBC Act to achieve its objectives with extinctions continuing since the act was introduced in 1999.

- The EPBC Act has no compulsory mechanism to address the cumulative impacts of species decline including the loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitat, the threats posed by invasive species and the effects of climate change.

- The framework of the EPBC Act is not adequate to address the drivers of species decline plus there have been significant failures in its implementation, including use and resourcing of compliance and protection mechanisms, and that these would need to be addressed in a new or revised act.

- New environmental laws should be developed and there should be an independent institution with sufficient powers and funding to administer and oversee environmental approvals and compliance.

After the election the Senate granted the committee a further extension of time to produce a final report to 7 September 2020. We hope the Senate inquiry has some influence on the formal government processes and the funding available.

Review of EPBC Act

The federal government is undertaking a review of the chief biodiversity conservation law, the EPBC Act. It is led by Prof Graeme Samuel. A discussion paper can be found here.

The closing date for submissions has been extended to 17 April 2020.

The EPBC Act is more than 1000 pages of complex legislation, to which has been added over 400 pages of regulations. Clearly it is not fit for purpose of improving biodiversity into the future when we consider the outcomes of the past 20 years.

The Environment Defenders Office is calling for:

- A new Australian environment act that elevates environmental protection and biodiversity conservation as the primary aim of the act instead of the narrowly defined matters of national environmental significance.

- Duties on decision makers to exercise their powers to achieve the act’s aims.

- Two new statutory environmental authorities – a National Sustainability Commission and a National Environment Protection Authority.

- New triggers for federal protection action including activities that will impact on national reserve system (terrestrial and marine protected areas), ecosystems of national importance, vulnerable ecological communities, significant land-clearing activities, significant greenhouse gas emissions, significant water resources (beyond coal and gas project impacts).

- A dual focus on protection and recovery of threatened species and ecological communities.

- A national ecosystems assessment and environmental data and monitoring program that links federal, state and territory data.

- Greater emphasis on indigenous leadership, land management and biodiversity stewardship, including formal recognition of indigenous protected areas.

- A suite of international conservation protections to ensure Australian governments, companies, citizens and supply chains protect and support global biodiversity.

One of the stumbling blocks is the mindset held by governments and business that decisions should be made quickly to reduce ‘green tape’. The value of the environment has to be elevated above the value of development at any cost.

Lord Howe Island Rodent Eradication Declared a Success

After a prolonged process of research, impact assessment, economic analysis and discussion with residents the Lord Howe Island Board got the go ahead for the rodent eradication program – see STEP Matters Issue 191.

It was estimated there were 150,000 rats and 210,000 mice on Lord Howe — some 1,000 rodents for each of the island's 350 residents. Lord Howe Island is home to many threatened, endemic and migratory species. Rodents have previously caused the extinction of five bird and 13 invertebrate species on the island and currently threaten another 70 species.

One area of concern about the widespread use of baits was the risks to the island’s unique wildlife, particularly two endemic species of bird, the Lord Howe Island woodhen and the currawong, that might be particularly at risk of eating the bait. The former is an endangered bird, which was nursed back from the brink of extinction on the island in the 1980s — only a few hundred exist. The two species were taken into captivity while the rodent eradication program took place — placed in cages and looked after by staff from Sydney's Taronga Zoo.

Baits being used in the past to control the rodent population have proven to be ineffective largely because the program was too limited and most of the island is inaccessible. The program had to be much more comprehensive. In June the project commenced when cereal pellets laced with poison were placed inside 22,000 lockable traps distributed around the island. Inaccessible areas were targeted by aerial drops of the same bait.

There was a rapid reduction in the number of rodents at first, and then a few little blips of activity. The last set of baits was distributed in November. The island will be monitored for two years, and if no rats or mice are spotted, the area will be declared rodent free. So far it appears the project has been a resounding success.

Return of the Phasmid

Return of the Phasmid

If the rodents are eliminated it should be possible to reintroduce the world’s rarest insect, the Lord Howe Island phasmid or stick insect. This giant is about the length of an adult’s palm when fully grown. It lives in communities, from a few dozens to several hundreds, in hollow trees.

In the early nineteenth century the insect was common but the rats found them very palatable so they disappeared in about 20 years. They were believed to be extinct until, in 2001, a group of scientists managed to climb onto the precipitous Ball’s Pyramid, a rock island 20 kilometres away. Several specimens were collected but only two survived. The female nearly died but intensive care enabled her to survive and lay several eggs. She has provided the insurance population but with a lack of genetic diversity.

Another expedition was undertaken in 2019 using professional climbers. The exploration had to be carried out at night as the phasmid is nocturnal. After a week only 17 insects were found. The low numbers may be because these insects only eat one plant, Melaleuca howeana. The museum had a permit to take no more than 10% of them so one precious specimen was taken back to Melbourne Zoo. She is now busily laying eggs.

In about two years’ time it is hoped they will be released onto Lord Howe Island.

Australia's Climate Change Policies

At the start of the bushfires right up to December the government refused to talk about the influence of climate change on the drought and bushfires – ‘now is not the time’, etc.

Seriously!

Australia’s current climate change polices are woefully inadequate. So much so that they were ranked 57th out of 57 countries in a report by The 2020 Climate Change Performance Index prepared by a group of international thinktanks that looked at national climate action across the categories of emissions, renewable energy, energy use and policy.

On the assessment of national and international climate policy, Australia is singled out as the worst-performing, with the report saying the re-elected Morrison government:

has continued to worsen performance at both national and international levels.

As the fires worsened the government’s stonewalling became stronger still trotting out the tired old excuses; we are only 1.7% of world-wide emissions. we will make our 2030 target ‘at a canter’, we are doing better than other countries on a per capita basis, etc.

In response to the criticism the statement from PM Morrison that policies are ‘evolving’ does not engender confidence that any meaningful changes will be made.

I don’t want to bore the reader with a lot of technical detail but I will try to provide a brief fact check on progress in meeting emissions reduction commitments and the effectiveness of current policies in one place.

Emission Reduction Targets Explained

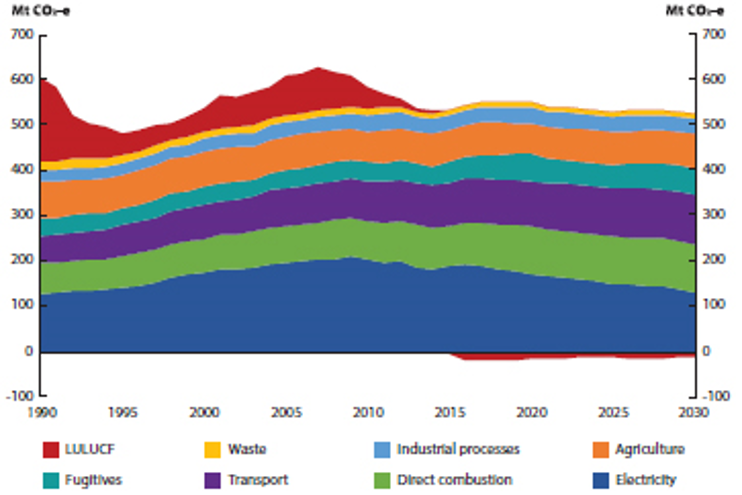

The reports from the Australian Department of Environment and Energy provide detailed explanations of the sources of emissions and projections through to 2030. The past data is constantly updated which can be confusing. I am using the latest report called Australia’s Emissions Projections 2019 published in December 2019.

Carry Over Credits

The original Kyoto Protocol commitments were based on data of greenhouse gas emissions during 1990. Australia managed to negotiate a favourable position whereby the base year data included emissions from land use, land use change and forestry. It just so happened that there was a high rate of land clearing in Queensland in that year so we had an unusually high baseline.

Australia’s first commitment for the 2008–12 period was an allowance for average emissions to increase by an average of 8% compared to 1990 levels, unlike most countries that committed to reduce emissions by at least 5%.

As it happened, we managed to over-achieve the target emissions and ended up with a carryover credit of 128 Mt CO2-e.

The next commitment was made to reduce emissions compared to 2000 levels by 5% to 2020. The way this is described implies that the level at 2020 should be 5% below the 2000 level. In fact, the requirement is that the total emissions over the 8-year period 2013 to 2020 should be 5% less than 8 times the level in 2000. The data cannot be quite finalised yet but it looks as though this commitment will be over achieved by around 280 Mt CO2-e. The total carryover is then of the order of 400 Mt.

The next target to focus on is the commitment made under the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions by 26 to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. Again, this means that the total emissions over the 10-year period 2021–30 will be 26 to 28% below ten times the level in 2005.

The government’s own advisory body, the Climate Change Authority advised in 2015 that the science-based target should be between 40 and 60% below 2000 levels based on a goal of keeping global temperature below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

How are Emissions Tracking?

How are Emissions Tracking?

The latest government report states that the 2005 emissions level was 602 Mt CO2-e. So, the total emissions allowance for 2021–30 is 4,778 to 4710 Mt (602/1.26x10 to 602/1.28x10) (see figure which shows Australia’s emissions 1990–2030).

Emissions in 2020 are estimated to be 534 Mt and in 2030 511 Mt. The current projections are that emissions over the 10 years will be 5,169 Mt, at least 390 Mt over the commitment. We can only achieve the commitment if use is made of the carryover credits of 400 Mt.

Taking advantage of these credits is very poor form. No other country is doing this. Most of the rest of the world is genuinely taking action to reduce their emissions. What matters is emissions now and the path to zero emissions by 2050, not the easy ride we were given last century.

2050, not the easy ride we were given last century.

Climate Policies

The policies to reduce emissions are:

- Renewable Energy Target (RET)

- direct action under the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

- safeguard mechanism

- National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP)

It doesn’t appear that these policies, particularly the ERF, are sufficient to achieve our 2030 target, particular given that many do not currently appear to have sufficient funding.

Renewable Energy Target

The original RET was established with the goal of increasing generation from renewable electricity sources compared with the level in 1997 to 20% by 2020. In practice the goal was expressed as 41,000 GWh of electricity generated per year.

The Abbott Liberal Government claimed the cost was too high and instituted a review by the Climate Change Authority. As a result, the target was reduced to 33,000 GWh by 2020 equivalent to about 23.5% of the current total of electricity demand.

Despite the dramatic rhetoric from the politicians supporting coal-fired power, the cost of providing incentives for renewable electricity generation has increased bills by only about 5%.

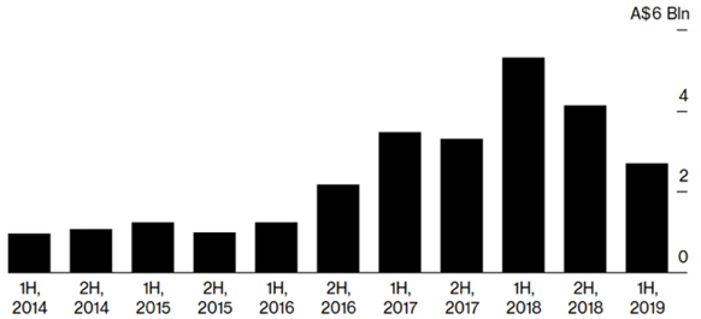

This target has been achieved already in 2019. No announcement has been made of any future policy creating great uncertainty in the industry. There has been a drop in new investment of nearly 21% in 2018–19 (see figure) at a time when the technology is developing rapidly.

This target has been achieved already in 2019. No announcement has been made of any future policy creating great uncertainty in the industry. There has been a drop in new investment of nearly 21% in 2018–19 (see figure) at a time when the technology is developing rapidly.

Several states have announced renewable energy targets so it looks as though it is up to the states to encourage new renewable energy projects. The take-up of rooftop solar is also still strong. Data from CSIRO and AEMO confirms that, while existing fossil fuel power plants are competitive due to their sunk capital costs, solar and wind generation technologies are currently the lowest-cost ways to generate electricity for Australia, compared to any other new-build technology.

Continued renewables growth also requires long-term planning of transmission infrastructure and storage technologies to ensure the distributed energy can be delivered where it is needed, and that reliability is maintained.

Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

The ERF is a voluntary scheme designed to provide financial incentives for businesses, landholders and communities to reduce emissions. As of 16 November 2017, the ERF had contracted 189 million tonnes of emissions reductions at a cost of $2.23 billion. Around $300 million remained for government purchasing of emissions reductions. Further funding of $200 million pa has been agreed over the next 10 years.

A range of projects to reduce emissions have been funded under the ERF so far. These include, for example, projects to replace Melbourne street lights with more energy efficient light bulbs, native forest and vegetation regrowth projects and the use of gas from waste to create energy. Many have been criticised as an inefficient way of reducing our emissions, amid suggestions that the government is paying polluters for emissions reductions that would have happened anyway even without the scheme – see STEP Matters Issue 188.

Safeguard Mechanism

The ERF includes a safeguard mechanism, which aims to ensure that emissions reductions achieved by the ERF are not nullified by rises in emissions elsewhere. The safeguard mechanism came into effect on 1 July 2016, and encourages large businesses not to increase their emissions above historical levels. The mechanism applies to emitters with annual emissions of over 100,000 tonnes CO2-e. The mechanism has been criticised as weak as there is too much flexibility to allow companies to shift or adjust their obligations.

Energy Productivity

There is also a National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP) that aims to encourage more productive consumer choices and promote more productive energy services.

Measures listed in the NEPP include improved vehicle efficiency and improved residential building energy ratings and disclosure. The NEPP could result in reduced greenhouse gas emissions in numerous sectors including transport, agriculture, industry and electricity.

The NEPP is expected to contribute over one quarter of the emissions reductions required to meet our 2030 target. However, as of July 2016, there does not appear to be any additional funding specifically allocated to implement this plan. The plan appears to have a very low profile.

Book Review – Native Fauna of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

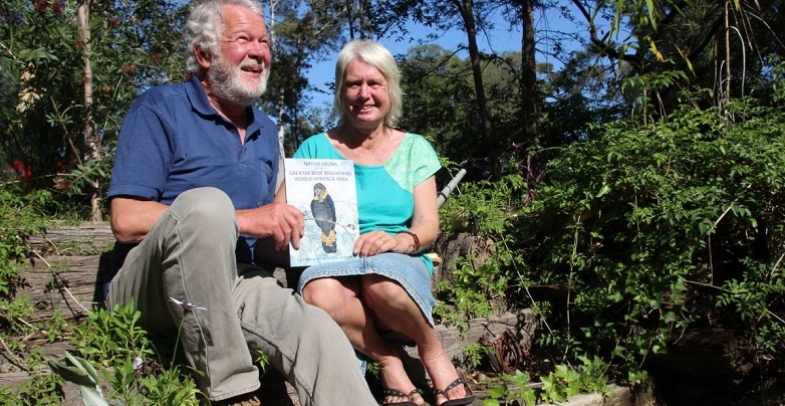

While we may stand on a clifftop lookout and gaze in awe at its world-class sandstone scenery, it wasn't the scenery or the geology but the flora and fauna that pushed the Greater Blue Mountains over the line in its world heritage listing. In an era in which we are easily distracted by technology and worrying world events not to mention frantically busy lives, this book is a balm to the spirit and a timely reminder that we have on our doorstep a region that is unique and biologically rich, and must be preserved at all cost. The work was compiled by veteran Blue Mountains ecologists whose names many of you will recognise from their comprehensive botanical surveys of the Hornsby Shire and other wild areas of greater Sydney.

Native Fauna of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area is far from the first publication on the topic in the region of course, but it compiles for the first time in one volume all the mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds that have been recorded in that vast and physically challenging area. It does this with many compact but excellent photos, and also with summary descriptions of sightings, key habit and habitat information and conservation status. Plus there is a full index and comprehensive reference list.

The impact of the book is further lifted however by more than 25 beautiful watercolours by Kate Smith. These not only are accurate representations of their subjects but have a pleasing softness that contrasts with the many sharply-defined photographs taken by Peter Smith. This is a must buy for anyone with an interest in Blue Mountains natural history and should sell at least many hundreds of copies. It's available in Blue Mountains bookshops and information centres (there are many) so buy a copy next time you're up there.

Judy, Peter and Kate Smith

P&J Smith Ecological Consultants

published 2019, 172 pp, full colour, $35

Review by John Martyn

Infrastructure Cannot Catch Up with Current Population Growth

The state and federal governments are unwilling to discuss the issue of Australia’s population growth. The general view is that the greater the growth the more we will all benefit. Of course their only interest is the simple notion of economic growth, not social wellbeing or environmental quality. Actually economic growth has not been great either. The fact that economic growth per capita has not kept up with inflation has been conveniently ignored.

Australia’s population grew by an average of 400,000 over each of the last five years to reach 25.4 million at 30 June 2019. 60% of this growth is from net overseas migration. This is adding another Canberra every year. The prospect that our population could reach 60 million by the end of the century doesn’t seem to worry the politicians. They appear to believe that this is a fact of life.

Sustainable Population Australia commissioned a report on the infrastructure needs of Australia following the increase in our growth rate this century. The report by Leith van Onselen from business analysis firm Macrobusiness found that unless Australia's population growth is substantially reduced, it is an illusion to believe that infrastructure will ever catch up.

Amenity for people in our major cities is being eroded through increasing congestion and road tolls, declining housing affordability and loss of green space. The whole country is having to bear the growing infrastructure costs.

The report estimates that each additional person requires at least $100,000 worth of additional public infrastructure to maintain the current standard of living. Governments have been trying to catch up with a backlog of infrastructure that developed during the early part of this century. Some progress is being made but we will be forever trying to catch up to cater for the new residents.

The Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics estimated that congestion costed the Australian economy $16.5 billion in 2015. Moreover, without major policy changes, congestion costs are projected to reach $27 to $37 billion by 2030. Similarly, Infrastructure Australia, in its 2019 infrastructure audit, estimated that the annualised cost of traffic congestion and public transport crowding in Australia would rise from $19 billion in 2016 to $39.6 billion in 2031. These congestion pressures will be particularly acute in Sydney and Melbourne.

The cold hard truth is that the quantity of infrastructure investment required for a big Australia is mind-boggling.

The volume of population growth into Sydney and Melbourne needs to be put into perspective:

- It took Sydney roughly 210 years to reach a population of 3.9 million in 2001. Yet the official medium projection by the ABS has Sydney reaching roughly 2.5 times that number of people in only 65 years.

- It took Melbourne nearly 170 years to reach a population of 3.3 million in 2001. The official medium ABS projection, however, has Melbourne’s population tripling that number in only 65 years.

In the face of these unprecedented numbers, the key difference between then and now needs to be underlined: unlike the post-war period, it is no longer easy to further expand the capacities of our largest cities. What was an abundant supply of cheap frontier land in the 1950s and 1960s is now well and truly built-out. Both cities are now sprawling metropolises with greenfield land in short supply. Ever-longer commutes erode productivity, and ever-greater distances between rich and poor neighbourhoods entrench disadvantage. New infrastructure investment necessarily requires costly solutions like land acquisitions and tunnelling in order to retrofit projects into existing suburbs.

Some recent examples are stark. The WestConnex project in Sydney will reportedly cost $17 billion for 33 km ($515 million per kilometre) while Melbourne’s West Gate Tunnel is expected to cost $6.7 billion for five kilometres of highway ($1.34 billion per kilometre). In contrast, the 155 km Woolgoolga to Ballina highway upgrade, a surface road, costs $4.9 billion, or just $32 million per kilometre (approximately 16 times less than WestConnex, and 42 times less than the West Gate Tunnel, on a per kilometre basis). And yet, with all of this current and proposed investment, of increasing orders of magnitude, congestion is still expected to increase.

The Productivity Commission has reported several times on the costs and benefits of immigration and has found little if any net benefit for the existing population. It has also added an important caveat, namely that it has not taken the infrastructure or environmental costs into its analyses because of the complexity of doing so

There are two myths that the government keeps on spruiking as the solution. Again these were the findings of a COAG report.

Invest in Infrastructure and Plan Better

The SPA report demonstrates that this is impossible with the current growth rate.

Settle New Migrants in Regional Areas

There is no way of keeping migrants in regional areas when there is not enough employment. Cutting Sydney’s population by 40,000 would not be noticed but the addition of that many people to a centre like Orange would double its current numbers. Most regional centres do not have enough water supply to cater for a large increase in population. Much of regional Australia is located far away from the ocean, meaning that desalination of seawater is not an option, and large-scale desalination of groundwater for inland towns is unlikely to be feasible or ecologically sustainable.